- Joined

- Aug 2, 2013

- Messages

- 1,154

Front Surg. 2014 Jun 20;1:22. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2014.00022

Successful Treatment of Colorectal Anastomotic Stricture by Using Sphincterotomes

Tzu-An Chen 1,*, Wei-Lun Hsu 2

PMCID: PMC4286977 PMID: 25593946

…

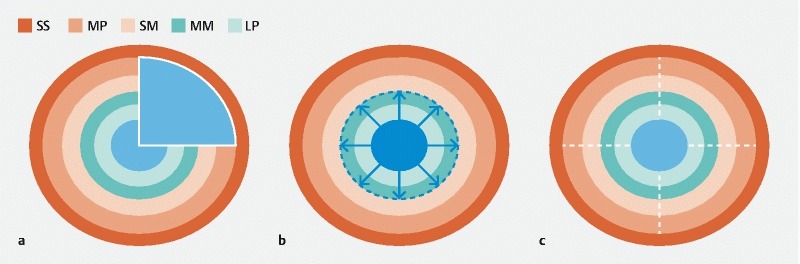

Endoscopic incision for the treatment of anastomotic stenosis in the upper gastrointestinal tract is well accepted (14), but its application for colorectal anastomotic strictures is limited. The sphincterotome is a bow-like device, which has an electrosurgical cutting wire at the distal end of the catheter. A monopolar power source is connected to the catheter at an electrode connector on the handle. During a sphincterotomy activation of the power source causes electrical current to pass along an insulated portion of the wire within the catheter to the exposed cutting wire. A retractable plunger on the control handle permits flexing of the catheter tip upward by pulling on the cutting wire. This flexing assists with aligning the cutting wire and maintaining contact of the wire with the scarred anastomosis while the catheter is pulled back, incising the circular scar of anastomosis by electrocauterization. Because of the bilateral plastic limbs of the sphincterotome, the depth of electrocauterization was limited and perforation of bowel wall could be avoided (Figure 3). We made three or four incisions at different directions to release the stricture. The purpose of the incision was breakdown of the membranous circular scar, and we preferred multiple shallow incisions but not one deep incision with curative intent. We believe that if the strength of stricture was released by multiple incisions, the lumen would be dilated by the following stool passage. One curative deep incision was not necessary so the risk of bowel injury could be diminished.

Some authors also reported small case series about using endoscopic incisions plus balloon dilation for the anastomotic stricture (15, 16). Based on our result, additional balloon dilation might not be necessary if the multiple incisions were completed and the membranous scar was demolished. Recently, some authors tried to treat benign colorectal strictures by stenting (17). Although the use of self-expanding metal stents to treat obstruction colorectal tumors has been commonly described in the literature, the application of stenting to benign stricture is uncommon. The long-term reliability of stenting is questioned; migration, erosion, pressure necrosis, and bleeding all have been reported (18). In our opinion, endoscopic self-expanding metal stent placement as a bridge to surgery is an option for acute malignant colonic obstruction. For the long-term usage in benign anastomotic stricture, colonic stenting is not encouraged.

Chen TA, Hsu WL. Successful treatment of colorectal anastomotic stricture by using sphincterotomes. Front Surg. 2014 Jun 20;1:22. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2014.00022. PMID: 25593946; PMCID: PMC4286977.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4286977/

Front Surg. 2014 Jun 20;1:22. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2014.00022

Successful Treatment of Colorectal Anastomotic Stricture by Using Sphincterotomes

Tzu-An Chen 1,*, Wei-Lun Hsu 2

PMCID: PMC4286977 PMID: 25593946

…

Endoscopic incision for the treatment of anastomotic stenosis in the upper gastrointestinal tract is well accepted (14), but its application for colorectal anastomotic strictures is limited. The sphincterotome is a bow-like device, which has an electrosurgical cutting wire at the distal end of the catheter. A monopolar power source is connected to the catheter at an electrode connector on the handle. During a sphincterotomy activation of the power source causes electrical current to pass along an insulated portion of the wire within the catheter to the exposed cutting wire. A retractable plunger on the control handle permits flexing of the catheter tip upward by pulling on the cutting wire. This flexing assists with aligning the cutting wire and maintaining contact of the wire with the scarred anastomosis while the catheter is pulled back, incising the circular scar of anastomosis by electrocauterization. Because of the bilateral plastic limbs of the sphincterotome, the depth of electrocauterization was limited and perforation of bowel wall could be avoided (Figure 3). We made three or four incisions at different directions to release the stricture. The purpose of the incision was breakdown of the membranous circular scar, and we preferred multiple shallow incisions but not one deep incision with curative intent. We believe that if the strength of stricture was released by multiple incisions, the lumen would be dilated by the following stool passage. One curative deep incision was not necessary so the risk of bowel injury could be diminished.

Some authors also reported small case series about using endoscopic incisions plus balloon dilation for the anastomotic stricture (15, 16). Based on our result, additional balloon dilation might not be necessary if the multiple incisions were completed and the membranous scar was demolished. Recently, some authors tried to treat benign colorectal strictures by stenting (17). Although the use of self-expanding metal stents to treat obstruction colorectal tumors has been commonly described in the literature, the application of stenting to benign stricture is uncommon. The long-term reliability of stenting is questioned; migration, erosion, pressure necrosis, and bleeding all have been reported (18). In our opinion, endoscopic self-expanding metal stent placement as a bridge to surgery is an option for acute malignant colonic obstruction. For the long-term usage in benign anastomotic stricture, colonic stenting is not encouraged.

Chen TA, Hsu WL. Successful treatment of colorectal anastomotic stricture by using sphincterotomes. Front Surg. 2014 Jun 20;1:22. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2014.00022. PMID: 25593946; PMCID: PMC4286977.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4286977/